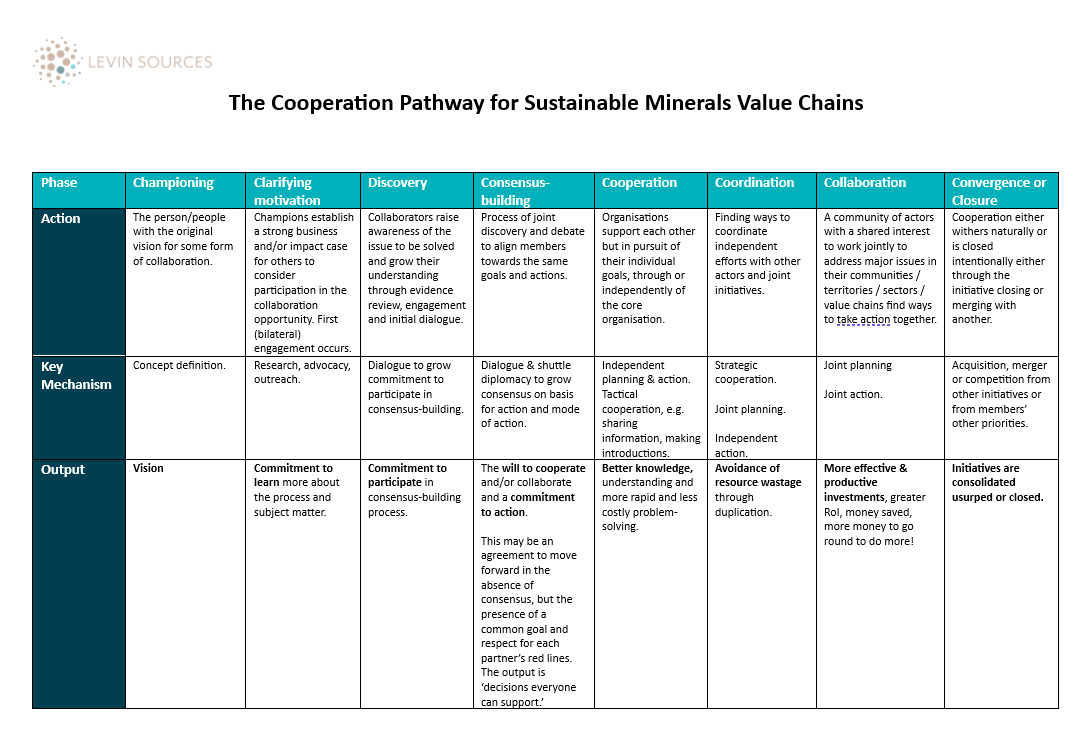

Global challenges can’t be addressed without effective cooperation. We’ve developed the Cooperation Pathway for Sustainable Minerals Value Chains to help our stakeholders consider where they are in their journey to solving those big problems that can’t be resolved alone. It helps you see what needs to be strengthened to cooperate better, or identify where there is or may be duplication of effort, resource wastage or competition that is getting in the way of addressing a shared goal.

The Pathway is particularly applicable to multistakeholder processes seeking to align diverse stakeholders to take complementary or joint action to address a common issue or opportunity. For example, how can downstream actors and their investors address the severe ecological impacts of critical minerals production in Indonesia, Brazil or Zambia? How can the West African gold mining community address the cumulative impacts of their activities on the transboundary Faleme River? What should national women’s collectives prioritise when pushing for changes to policy and culture? It can also be used as a tool within companies to build greater alignment and cooperation on the contentious issues, like dealing with community conflict or artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM).

The lightbulb came in early 2024 during our research for a Call to Action for policymakers published by the Global Battery Alliance on how to Bridge the cooperation gap in critical battery minerals with harmonised data and transparency. When we were designing the GBA’s first pioneering Key Performance Indicators for the Battery Passport in 2021-2, my colleague, Johannes Drielsma, developed a fantastic tool called the GBA Consensus Way based on the application of Systemic Consensing. He used this to help his multistakeholder working group work through points of contention and disagreement that inevitably arose when crafting the Greenhouse Gas Rulebook. And as we were researching the elements on scaling critical battery minerals supply sustainably this year, we, in consultation with the Global Battery Alliance members and Secretariat, came to realise that it’s a struggle to cooperate if you don’t have consensus. We then went on to develop the thought - is there a pathway?

Here are suggestions of how you could use the Pathway based on four dimensions where we need to get better at cooperation to drive sustainability in minerals value chains.

1 - Within territories

In mining landscapes (e.g. Keyes in Mali, the Iron Quadrangle in Brazil, Maluku Island in Indonesia), deeper cooperation with government, other economic actors, and communities, can help miners and smelters avoid and minimise harms and capture opportunities to really convert the mineral endowment into sustainable development.

For example, more equitable structures for mining ownership and governance require experimentation in deeper collaboration to secure the social licence to operate as well as more sustainable outcomes for present and future generations of mining-impacted communities. ‘Fair share’ or ‘benefit sharing’ agreements are increasingly the norm in Canada, with First Nations finally beginning to enjoy full(er) participation in equity and decision-making. This tightening of relations requires deep collaboration between landowners or managers, like Indigenous peoples and local communities, and mineral licence holders, beyond what has been the norm in mining globally. Yet, we have some way to go; an interview with a First Nations leader was sobering regarding the extent to which Canada’s Indigenous peoples would consider these agreements to be equivalent to consent.

Circularity in mining is a huge opportunity for mitigating adverse impacts on people and nature, and for unlocking new economic opportunity for miners and their stakeholders. Yet our research has shown that it is being pursued haphazardly and fairly unimaginatively. Konstantin Born, an expert in circularity in mining, argues that miners struggle with becoming more circular because it requires greater cooperation with economic actors, governments, and local communities to bring an innovative solution to life – whether nature-based solutions for water purification or exploring new economic models such as minerals as a service. A barrier to greater circularity is developing the skills, resources and commitment we need to navigate what can be quite complex cooperations.

Industrial mines operating in the same territory can pool resources and power to take action on joint challenges, whether that’s lack of hazardous waste solutions, climate change adaptation, securing women’s rights, or addressing ASM booms, and so forth.

2 - Within sectors and value chain tiers

A miner or a refiner may have a choice of standards or may supply mineral off-takers with diverse requirements as to which standard the supplier should conform with. A lack of harmonisation of standards and diverse conformance and reporting expectations across multiple clients and multiple financiers create an enormous burden on business, sucking resources away from the most important step in due diligence – prevention, minimisation and mitigation of risks.

- The Consolidated Mining Standard Initiative will help address this.

- Our client, Drive Sustainability, is also a platform for cooperation and collaboration amongst automotive companies as they pool resources to do joint risk identification, mitigation preparedness and reporting.

These processes show how companies are increasingly coming together in a pre-competitive fashion to address joint challenges and mitigate risks to people and nature. Unfortunately, in the US anti-ESG movement is using antitrust legislation to challenge industry cooperation by issuing subpoenas to hinder activities such as information sharing, standard-setting, sectoral collaborations and engagement. By contrast, the EU has issued market guidance on how to advance pre-competitive collaboration within battery charging markets to address competition risks.

3 - Across value chains

Downstream actors frequently impose their demands on suppliers, taking a policing not partnership approach. This is challenging for small businesses, businesses operating in higher risk jurisdictions or where legal standards are far below international ones – the stretch is just too much, so why bother? This is why the United Nations Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights and the OECD Responsible Business Conduct and Minerals Guidances advocate for downstream actors to partner with their suppliers to jointly manage the salient supply chain risks (building mutual capacity as they do so). This is how we’ll drive broader socio-economic advancement.

4 - Across political divides

Ideological and geopolitical divergence are barriers to cooperation and tackling global issues in partnership with ‘hostile’ blocs, whilst intensifying cooperation within blocs. The race to secure access to critical minerals is an example. The most sustainable path forward would be to leverage assets and strengths across these blocs, though of course this is frequently politically infeasible. However there are examples of western and eastern businesses partnering, to drive the just energy transition (e.g. the China-based XTC New Energies Group and majority French state-owned Orano joined forces to manufacture battery components in 2023).

The domestication of international conventions creates inefficiencies in trade, another domain where greater cooperation could address bottlenecks. For example, differing domestic interpretation of the Basel Convention’s classifications of hazardous waste is creating barriers to trading waste batteries, so preventing their relocation to the optimal markets for reprocessing and materials recovery. Work is needed to align and standardize those interpretations, which will require dialogue, consensus-building and eventually joint work to improve coordination between trading partners.

***

The Cooperation Pathway for Sustainable Minerals Value Chains offers an opportunity to level the playing field and tackle joint solutions in ways that are more inclusive, more cost-effective, and more sustainable. It requires strong leadership and a robust process as the basis for building trust across different interests. Mining is the least trusted sector, even after tobacco and oil and gas. If we get better at cooperating we can be better at addressing some of the issues that give our industry such a bad reputation, and we can start to rebuild trust with our stakeholders. Let’s work together.

The Cooperation Pathway for Sustainable Minerals Value Chains © 2024 by Estelle Levin-Nally, Levin Sources is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

**

Sources and further reading on consensing and cooperation:

The Breakthrough Agenda Report 2024 (iea.blob.core.windows.net) (GBA mentioned on 87-89)

Konstantin Bonn (2024) Exploring the Spatial Dynamics of Circular Economy Transitions: Insights and Lessons from Chile's Mining Territories, unpublished manuscript.

Business Konsens International Network (n.d.) SK-Principle® At https://businesskonsens.eu/en/sk-principle_systemic-consensing-methode/

Johannes Drielsma and Volker Visotshnig (2023) Systemic Consensing (SK-Prinzip®) for building Trust. At https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j7EEi2pnzeA (Responsible Raw Materials)

Global Battery Alliance (2024) The Global Battery Alliance Call to Action: Policymakers to bridge the cooperation gap in critical battery minerals with harmonised data and transparency. At gba-cmag-communique-final-june24.pdf

Bernard E. Harcourt (2023) Cooperation: a political, economic and social theory (Columbia University Press)

Debbie Mashek (2023) Collabor(h)ate: how to build incredibly collaborative relationships at work (Practical Inspiration Publishing)

Jean Oelwang (2022) Partnering: forge the deep connections that make great things happen (Ebury Edge Publishing)

WEF. Partnerships can help scale and accelerate circularity: here’s how. 19 September 2023. At https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/09/partnerships-help-scale-accelerate-circularity-sdim23/

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Konstantin Born, Dr. Johannes Drielsma, Louis Marechal, Dr. Fiona Solomon and Kaisa Toroskainen for their reviews of an earlier draft and contributions that helped me finalise this blog.